A Need-Based Perspective on Increasing Returns

Note: This is an excerpt from the post “Big Picture DevOps through the Ofmos Lens” on the Ofmos Blog, enhanced here with additional illustrations.

Header image: Cristian Mitreanu, The ‘Increasing Returns’ Balloon Analogy (November 2021).

Hi-tech products, and particularly software, have long been associated with an anomalous behavior referred to as “increasing returns” (as opposed to “diminishing returns,” where growth slows down over time and the profit margins drop). In his 2016 Fast Company article “A Short History of the Most Important Economic Theory in Tech,” Rick Tetzeli observes that “the theory of increasing returns is as important as ever: It’s at the heart of the success of companies such as Google, Facebook, Uber, Amazon, and Airbnb.”

W. Brian Arthur, who popularized the concept with his 1996 Harvard Business Review article “Increasing Returns and the New World of Business,” describes increasing returns as ”mechanisms of positive feedback that operate — within markets, businesses, and industries — to reinforce that which gains success or aggravate that which suffers loss. Increasing returns generate not equilibrium but instability: If a product or a company or a technology — one of many competing in a market — gets ahead by chance or clever strategy, increasing returns can magnify this advantage, and the product or company or technology can go on to lock in the market. More than causing products to become standards, increasing returns cause businesses to work differently, and they stand many of our notions of how business operates on their head.”

But how can that be? Ofmos theory tells us that every product commoditizes over time. Simply put, every product loses some of its perceived value relative to a set of customers with the same product-associated behavior, as the product knowledge accumulates within that business space (i.e., offering-market cosmos or, short, ofmos) over time. Does the concept of increasing returns imply that some products defy “business Gravity”? Or is that just an illusion?

[SIDEBAR> THE POSTULATES OF THE OFMOS THEORY

Developed to provide an explanation of a particular aspect of the natural world, a theory typically rests on a set of fundamental assumptions that are accepted to be correct or true without the need of proof. In mathematics, these assumptions are called “postulates” (i.e., Merriam-Webster Dictionary: “postulate: a hypothesis advanced as an essential presupposition, condition, or premise of a train of reasoning”) and, for illustrative purposes, I will use the same term here. If nature does not agree with the postulates or the theory, they might need to be revisited.

In my 2018 RedefiningStrategy.com article “A Natural Theory of Needs and Value,” I describe the POSTULATES OF THE OFMOS THEORY, as they were first articulated in the original 2007 RedefiningStrategy.com article “A Business-Relevant View of Human Nature:”

All living things strive to perceive the composition of their environment.

All living things strive to make the most out of a given amount of resources, in a given moment.

All living things strive to remember the changes that occur within their environment.

These assumptions, through the theory built on them, give us the arrow of learning and, with it, the arrow of commoditization. In short, humans accumulate knowledge about something useful that they interact with inside a relatively closed system (i.e., a community), during a period of environmental stability. This learning and the associated collective learning gradually strips that useful something to its minimal functionality, thus reducing its perceived value (i.e., importance to the users). <SIDEBAR]

Let’s see. The Ofmos lens is showing us that, like the DevOps industry, all business spaces where providers address needs that are part of a customer process are likely to first evolve toward a platform offering. That means that the total market available to the providers at the beginning balloons first, as the number of needs served by the industry rapidly increases until the entire customer process is covered and an upper limit of a meaningful product integration is reached.

Borrowed from physicists, who use it to explain the expanding Universe, the “balloon analogy” (see image below) is an easy way to think how a faster-than-the-leader follower might fall further behind, when the space between them expands.

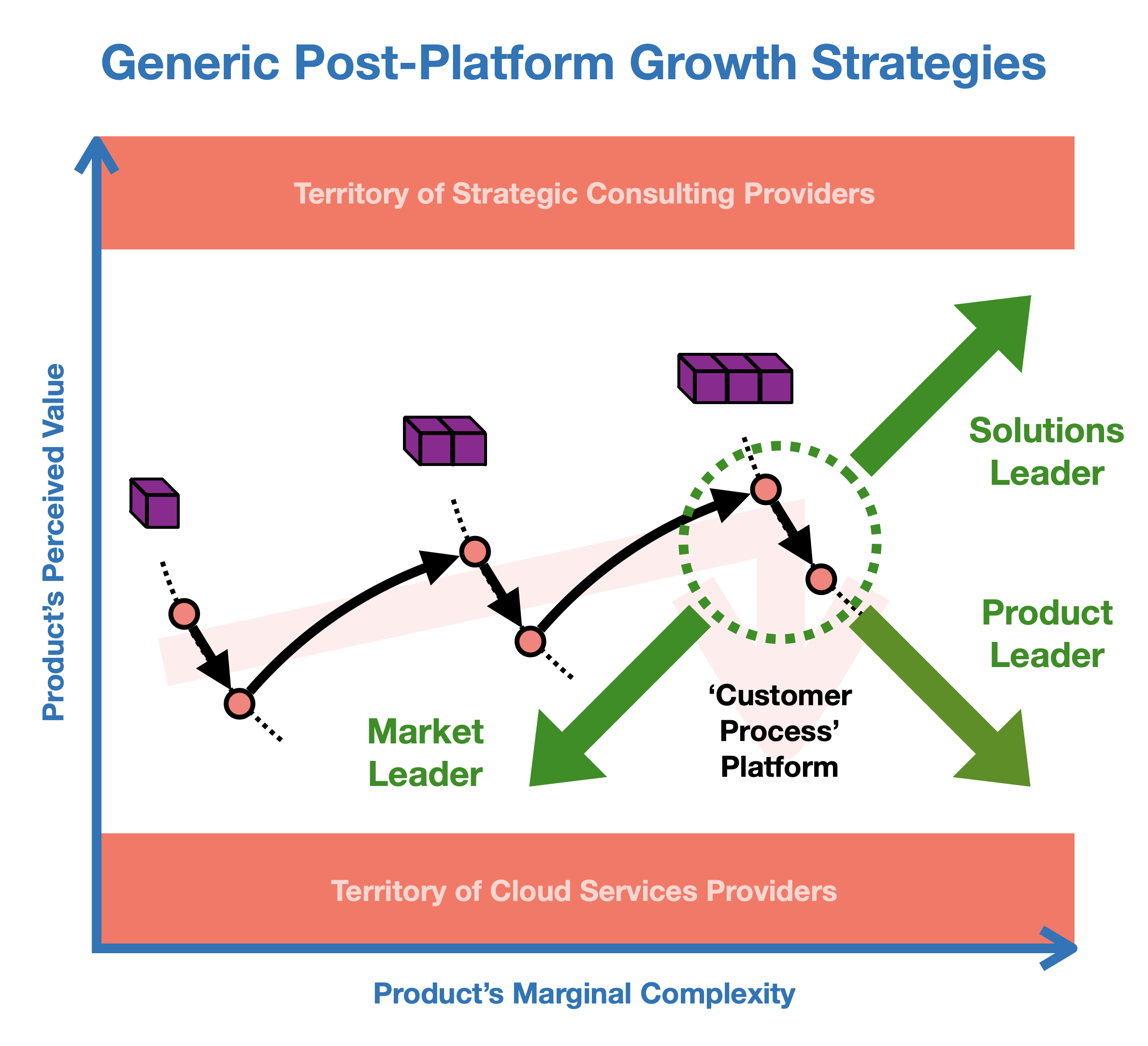

Indeed, from this perspective, it becomes apparent that an industry that centers around a multistep customer process goes through a first evolutionary stage characterized by increasing returns, which lasts until the entire customer process can be supported by a single product: a platform (see image below). At that point, the dynamics change and the industry enters a stage of diminishing returns, in which the market size stabilizes and a more traditional battle for market share ensues. The platform itself begins to commoditize.

Throughout the first phase, providers tend to develop their products and portfolios by adding new layers of functionality just like the layers of an onion around their initial offerings. This metaphor breaks down once the platform functionality is reached, however, and some managers and companies struggle. Throughout the second phase, a better metaphor is that of Picasso’s bull from his drawing study, shown in various levels of abstraction. Same core functionality, different add-on packages. Yet, finding the best way to navigate this evolving environment, which offers many possible strategic directions over time, is inherently difficult.

In his 2021 InfoWorld article “How Docker Broke in Half,” Scott Carey captures this struggle in the DevOps space with the dramatic story of the 10-year-old-company Docker, recently noting that, “the game-changing container company is a shell of its former self.” Quoted in the same piece, Google’s Kelsey Hightower observes that, “They put something out for free that nailed it, home run. They solved the whole problem and hit the ceiling of that problem: create an image, build it, store it somewhere, and then run it. What else is there to do?”

Something “unnatural” does appear to be at play here. And, to make things worse, Arthur’s characterization that, “more than causing products to become standards, increasing returns cause businesses to work differently,” seems to suggest that, instead of commoditizing, these products behave differently — a finding that, if true, would contradict our fundamental assumptions about human behavior. He even concludes the HBR article by saying that, “A new economics — one very different from that in the textbooks — now applies, and nowhere is this more true than in high technology.”

However, at a closer look, this apparent contradiction seems to stem from the way Arthur frames the products. In his original 1983 IIASA working paper “On Competing Technologies and Historical Small Events: The Dynamics of Choice under Increasing Returns,” he writes:

“Usually there are several ways to carry through any given economic purpose. We shall call these ‘ways’ (or methods) technologies and we will say that members of the set of technologies that can fulfill a particular purpose compete, if adoption of one technology by an economic agent tends to displace or preclude the adoption of another.”

“This use of technologies rather than goods as the objects of choice has a particular advantage. Where most goods show diminishing returns (in the form of increasing supply costs), very many technologies show increasing returns: often the more a technology is adopted, the more it is improved, and the greater its payoff.”

It is a looser, inward-looking (i.e., what are we building?) framing of the product that has been a key part of this body of work. In his 2013 Research Policy comment “Rerun the Tape of History and QWERTY always Wins — a Comment,” 30 years after his original article, Arthur uses various possible units of analysis or “objects of choice” interchangeably when talking about the concept, “Under increasing returns or decreasing costs, one product or technology or firm or standard or convention comes to dominate.”

This perspective, while consistent with the more practical view employed by providers and customers (i.e., as its functionality changes over time, an app remains largely perceived as the same product), could create some confusion — not only for those trying to understand the phenomenon, but also for the strategists in the field, who may inadvertently create the instability that Arthur has identified. Described by Theodore Levitt in his 1960 Harvard Business Review article “Marketing Myopia” as a case of losing sight of what customers really need, marketing myopia is likely to be more prevalent in these circumstances.

In the InfoWorld article mentioned above, Docker Founder and former CTO Solomon Hykes looks back and reflects, “I would have held off rushing to scale a commercial product and invested more in collecting insight from our community and building a team dedicated to understanding their commercial needs.”

Is this phenomenon an illusion, then?

Somewhat. The Ofmos lens shows that all products commoditize at a more detailed level — knowledge about the defining product accumulates inside an ofmos (offering-market cosmos), which causes the product’s perceived value to drop. At this level of analysis, increasing returns do not exist. It is only at a higher, coarse level that we see this phenomenon emerging. By aggregating needs and the corresponding products, we conflate together multiple business spaces, which leads to “unnatural” behaviors. In spite of their names, increasing returns and diminishing returns seem to be different categories of phenomena that are visible at different levels of granularity.

Nevertheless, furthering our understanding of increasing returns is important. Some 2,300 years ago, Aristotle observed that heavy objects fall faster than lighter ones — a rock falls faster than a feather. We now know that it is the air resistance that creates that illusion. Still, more insights into that “anomaly” eventually led to valuable contributions toward aviation and other useful areas. Similarly, by adding to our toolset a more nuanced, outward-looking (i.e., what needs are we addressing?) product framing, we could open a new chapter in our exploration of increasing returns, as it was shown here through the novel need-based perspective and the DevOps industry case.

And, finally, this new perspective gives us a nuanced and useful insight into how an industry — particularly a so-called business-to-business (B2B) space — evolves. From a “point solution” offering, we tend to see the action moving toward end-to-end platforms. …

Solutions Leader IBM,

Product Leader Blackboard

Market Leader

text