The 3D Product Model Canvas: Thinking and Strategizing in Volumes

Note: This is an excerpt from the posts “Generic Platforms in the Product Context” and “Software Products and the Concept of Platform,” both excerpts from the larger post “Big Picture DevOps through the Ofmos Lens” and both published on the Ofmos Blog for a higher visibility of the novel concepts and frameworks, with additional images and illustrations.

Header image: Shutterstock.

To begin, it is important to see the product as a collection of functional blocks that can be mapped inside a holistic, tree-dimensional space made up of all the “functionality requirements” volumes necessary for a product to be both functioning (i.e., technical viability) and addressing the customer needs (i.e., business viability). This space, inside which the product is being modeled as an assembly of functional parts that are placed in its various subdivisions, can be referred to as the 3D PRODUCT MODEL CANVAS.

// The word “canvas” is commonly used in business. Providing an easy metaphor for the process of defining a particular thing inside a general set of requirements (i.e., painting on canvas), it is part of the name of several product-focused frameworks (i.e., business model canvas, lean canvas, opportunity canvas, jobs-to-be-done canvas). The 3D Product Model Canvas is unique, however, as it captures both the functional blocks and the value creation flows that determine how these blocks are laid out — both essential elements in product strategy. Moreover, the 3D canvas can also be used to analyze and strategize at the product portfolio level, whether a company’s supporting architecture is monolithic or distributed (i.e., Web 3.0, Infrastructure as Code); thus providing a contemporary alternative to the decades-old concept of value chain, arguably the original business model framework. //

// This broader use case of the 3D Product Model Canvas — which stems from the one-need theory of behavior, as it is built backward from the customer needs — suggests that the tool can also be used as a business modeling tool. Think, the 3D Business Model Canvas. In her 2002 Harvard Business Review article “Why Business Models Matter,” Joan Magretta finds that:

business models are “stories that explain how enterprises work,”

“a good business model begins with an insight into human motivations and ends in a rich stream of profits,” and

“all new business models are variations on the generic value chain underlying all businesses.”

In their 2021 Journal of Management Studies article “What Can Strategy Learn from the Business Model Approach,” Lyda S. Bigellow and Jay B. Barney “posit that ultimately the business model approach, given its emphasis on interdependencies and multi-lateral connections, may provide more insight to managers and entrepreneurs who are grappling with the complexity of an increasingly interdependent environment in which to compete.” //

I first shared this “3D product model canvas” idea in my 2012 presentation “Unlocking Innovation in Education through Meaningful Technology (A General Model for Ed-Tech),” in which I introduce a general three-dimensional model [general model = canvas] for modeling an ed-tech product (slide 16 copied above), bringing together (a) the two-dimensional view of the customer-facing functionality and (b) the layered view of the architectural functionality. Even though the actual labeling of the architectural layers in this presentation is directly inspired by older structures (i.e., Web 2.0), the rationale for the 3D Product Model Canvas stands:

Holistically, the cube-shaped canvas should provide the outer boundaries for the entire product category that revolves around the customer process. Snapshots of any product in the category should be mappable inside it at any point in time, thus enabling strategic analyses and evolutionary roadmaps.

The canvas’ subdivisions should be framed around meaningful functionalities that stem from either customer needs or underlying architectural needs. They should be captured in MECE (mutually exclusive and collectively exhausting) lists and analyzed at the same level of granularity, providing inputs for competitive analyses and product strategy.

The layout of the subdivisions in the customer-facing layer should be dictated first-and-foremost by the flow of the customer process. (The presentation attempts to capture the additional, “tool scope” dimension and the data/information flow associated with it. And something interesting to be further investigated here is whether or not the customer-facing end-to-end functionalities tend to drift into the architectural layer underneath.)

The architectural layers should span the flow that stretches from raw data to useful information in the customer-facing layer.

To put it differently, the 3D Product Model Canvas captures and articulates the product functionality along the three main value creation flows, in a context where the customer benefits are the ends and the product is the means:

The Customer Value Creation Flow

The Organizational Value Creation Flow

The Architectural Value Creation Flow

// As mentioned, thinking in volumes is key here; and the world of car racing provides a simple-yet-powerful aid in that respect. For example, competitions like Formula 1 allow the participating teams to customize their cars — all within the boundaries set by the regulatory body, which aims to keep the field leveled. A major aerodynamic component, the rear wing, then, might only be constrained in terms of position and dimensions (width x height x depth). Inside that invisible box, each team develops its own unique solution. Different product models, same 3D canvas, and an easy way to switch to this way of thinking. //

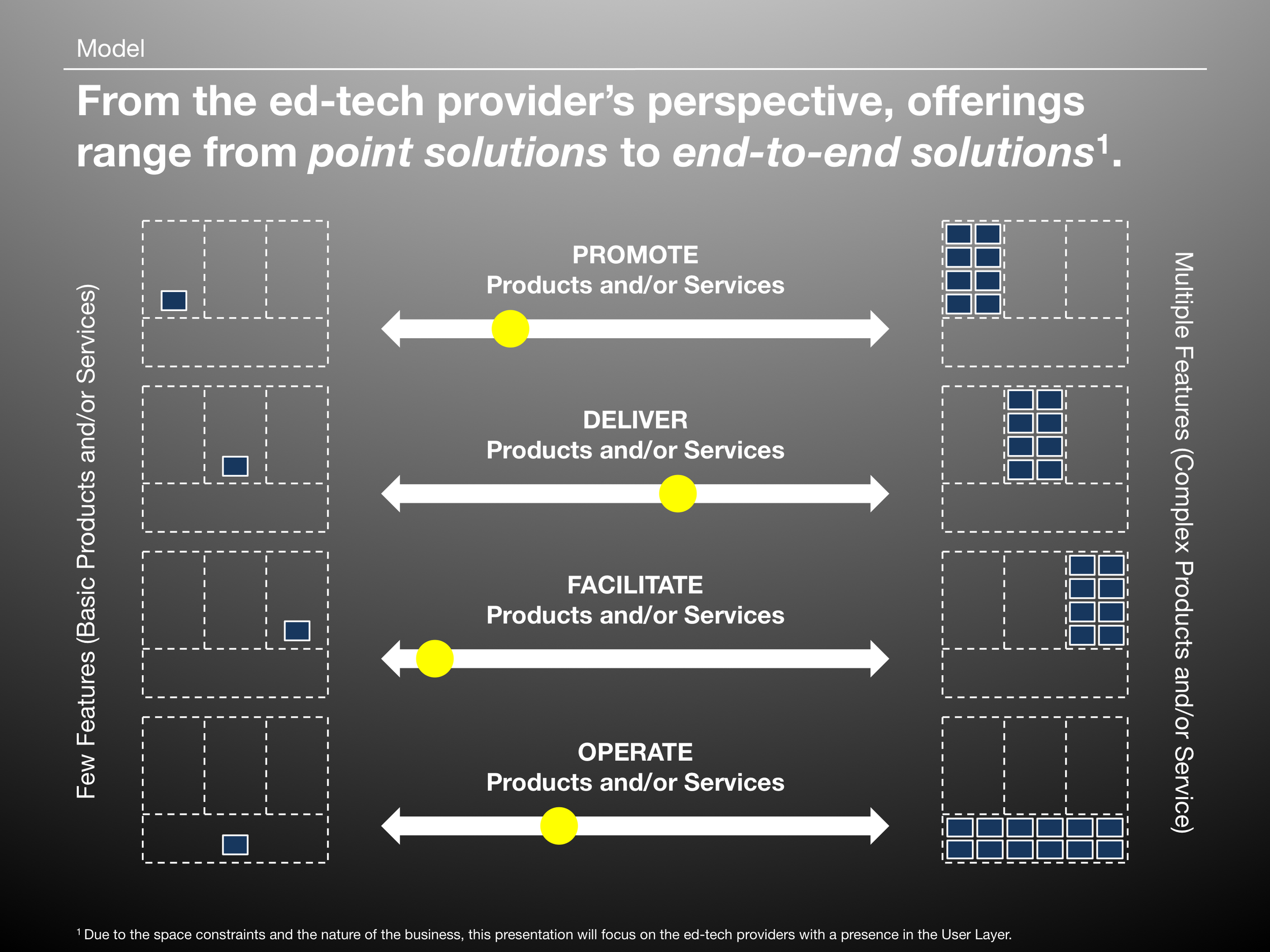

From this 3D product model canvas for ed-tech, then, a general 3D product model canvas can be readily generated by simply replacing the student life cycle with a generic customer process life cycle (i.e., sequence of interrelated tasks). Point solutions or complex products (slide 18 copied below, showing the customer-facing or top view of the 3D canvas), with monolithic or distributed architectures, can all be mapped and analyzed inside the 3D canvas.

The purpose of this cube-shaped functional representation of a product, which I simply call the 3D PRODUCT MODEL CANVAS, can be summarized by the two Herbert Simon quotes surfaced in the above-mentioned HBS paper: “Every problem-solving effort must begin with creating a representation for the problem” and “solving a problem simply means representing it so as to make the solution transparent.”

This structured approach to the customer needs and the corresponding product functionalities reveals where all major efficiencies (i.e., higher speed, shorter time) can be created. And it also reveals where the opportunities for creating economic lock-ins (i.e., monopolies) across and along the data/information flows are (see image below). As a result, it provides a clearer way of thinking about platforms in the product context: a basic unified set of functionalities that addresses all needs within a clearly-defined domain, allowing for further customer augmentation and offering economic lock-in to the provider.

(Note that, for simplicity, the below representation of the 3D Product Model Canvas does not illustrate the Organizational Value Flow, which is perpendicular on the Customer Value Creation Flow, and the associated functionality volumes.)

// It is important to keep in mind that the 3D Product Model Canvas, like other cognitive frames, could play an important role not only in the company’s strategy making process, but also in its political environment. In her 2008 Organization Science article “Framing Contests: Strategy Making Under Uncertainty,” Sarah Kaplan explains that, “Frames are the means by which managers make sense of ambiguous information from their environments. Actors each had cognitive frames about the direction the market was taking and about what kinds of solutions would be appropriate. Where frames about a strategic choice were not congruent, actors engaged in highly political framing practices to make their frames resonate and to mobilize action in their favor. Those actors who most skillfully engaged in these practices shaped the frame that prevailed in the organization.” //